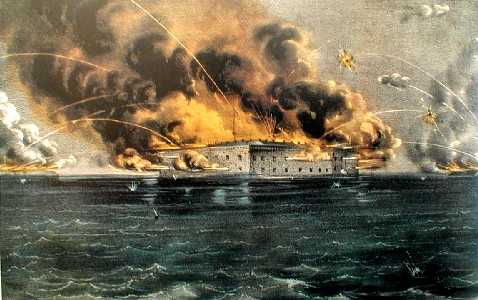

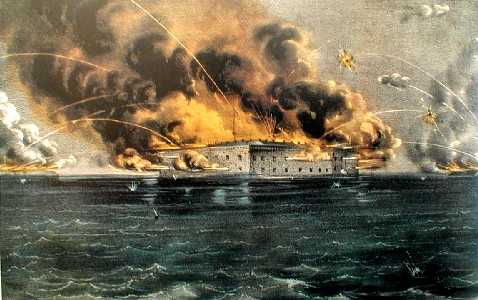

Fort Sumter and the Doctrine of States' Rights

Mood:

on fire

Now Playing: Eddie Condon's Dixieland All-Stars

Topic: Sumter and States' Rights

on fire

Now Playing: Eddie Condon's Dixieland All-Stars

Topic: Sumter and States' Rights

Fort Sumter and the Doctrine of States? Rights

April 12, 2005, will mark the 144th anniversary of the start of the American Civil War (henceforth ACW), also know as the War Between the States, and the War of Southern Secession. When it was all over, over 600,000 Americans would be dead. Ironically, many of the issues that sparked the blaze were not resolved at the end of the war, but continue to linger with us to this very day---such as the issue of States? Rights.

But first, some history.

One could argue that the ACW actually started on December 20, 1860 when South Carolina, distraught over the election of Abraham Lincoln, formerly passed an Order of Secession, a document remarkable for its lengthy legalistic rationale; in many ways, it is a strictly Southern Declaration of Independence. Contained within it are the justifications for the state?s drastic steps:

?The ends for which the Constitution was framed are declared by itself to be to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity.

These ends it endeavored to accomplish by a Federal Government, in which each State was recognized as an equal, and had separate control over its own institutions?.

We affirm that these ends for which this Government was instituted have been defeated, and the Government itself has been made destructive of them by the action of the non-slaveholding States. Those States have assume the right of deciding upon the propriety of our domestic institutions; and have denied the rights of property established in fifteen of the States and recognized by the Constitution?.?

Slavery, the blight that has plagued our fair land since its earliest days, reared its ugly head to ignite a war unlike any other this nation had witnessed. South Carolina, not willing to be consoled with an electoral loss that signaled a shift of power from South to North, felt itself obliged to do the unthinkable and leave the Union:

?We, therefore, the People of South Carolina, by our delegates in Convention assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, have solemnly declared that the Union heretofore existing between this State and the other States of North America, is dissolved, and that the State of South Carolina has resumed her position among the nations of the world, as a separate and independent State; with full power to levy war, conclude peace, contract alliances, establish commerce, and to do all other acts and things which independent States may of right do.?

Whether or not South Carolina?s decision to secede was rash, and I believe it was, the time for calm discourse had passed.

Events would now move quickly.

On December 26, Major Robert Anderson, seeing storm clouds on the horizon, prudently moved his small force from Fort Moultrie to the more easily defended Fort Sumter. The first shots would ring out approximately two weeks later on January 7, 1861, after Anderson had refused the demand of South Carolina?s governor, Francis Pickens, that the garrison surrender. Star of the West, a vessel laden with provisions, was fired upon as to prevent the victualing of Fort Sumter. Fortunately, the shots caused only minor damage to the vessel, but did force its withdrawal.

In a most remarkable show of restraint, President James Buchanan did not retaliate. However, his show of magnanimity would do nothing the stop the deepening crisis. More states soon followed South Carolina?s example. Mississippi on January 9, 1861; Florida on January 10; Alabama on January 11; Georgia on January 19; and Louisiana on January 26. On February 4, the Confederate States of American (CSA) became a political reality.

By March 4, when Abraham Lincoln took formal possession of the White House, six more states has seceded and only two forts, including Sumter, remained in federal control in all of the newly-created CSA. Lincoln, like his predecessor Buchanan, was determined not to provoke a war that he knew would tear the nation apart, perhaps for all time. As such, on April 8, with Fort Sumter running dangerously low on supplies, he notified Pickens that he would be sending a fleet of supply vessels, guaranteeing a cargo strictly limited to foodstuffs, with the intention of buying time for further negotiations.

On April 11, CSA President Jefferson Davis ordered General Pierre G. T. Beauregard to demand the fort?s evacuation before another attempt at provisioning was made. The unfortunate Anderson and his isolated men had their backs to the wall. His reply to Beauregard was that if he had not received victuals nor instructions from Washington by April 15, he would be forced to capitulate.

The CSA was not willing to wait.

On April 12, 1861, at 4:30am, like the first thunderclap of a long-expected summer storm, the war that all dreaded but none could stop arrived when Fort Johnson fired the initial volley in a bombardment that would last 34 hours. Ironically, Lincoln?s provisioning fleet arrived the very same day, but due to the intensity of the bombardment, was powerless to complete its mission. On April 14, Anderson surrendered the fort without the loss of a single man.

On April 15, a state of war was declared by the Lincoln administration, but no real fighting would take place until First Manassas, on July 21. But that is a story for another time?.

There are many tragedies to be found in the ACW. But perhaps the greatest is that the war would serve to undermine the cherished American principle of States? Rights, a doctrine that finds expression in the Tenth Amendment to the Constitution:

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

This idea was not some novelty snuck into the blueprint for our government, but a long-held belief dating back to the earliest days of the Republic. As Thomas Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence:

?We do assert and declare these colonies to be free and independent states, and that as free and independent states they shall hereafter have the power to levy war, conclude peace, contract alliances, establish commerce, and to do all other acts and things which independent states may of right do.?

Likewise, the Articles of Confederation states:

"Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right which is not by this Confederation expressly delegated to the United States."

Clearly, the first two forms of government that this nation created distinctly mentioned the fact that state government was held to be the primary form of government, and a national authority could only exist with the consent of the states. Furthermore, these states retained their right to reassume complete sovereignty at any time they deemed it necessary for the welfare of their people. A number of states even included explicit statements of state sovereignty in their constitutional ratification documents. New York State is a perfect example (emphasis mine):

?We, the delegates of the people of the state of New York...Do declare and make known,-

That all power is originally vested in, and consequently derived from, the people, and that government is instituted by them for their common interest, protection, and security.

That the enjoyment of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, are essential rights, which every government ought to respect and preserve.

That the powers of government may be reassumed by the people whensoever it shall become necessary to their happiness; that every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by the said Constitution clearly delegated to the Congress of the United States, or the departments of the government thereof, remains to the people of the several states, or to their respective state governments, to whom they may have granted the same?.?

It strain?s credulity to argue that states, which have traditionally maintained themselves to be the principle form of government among the American people, would suddenly enter into a compact which demanded a complete and perpetual surrender of power to a distant federal authority.

I think it was the great John C. Calhoun, having served as both senator and vice president during his political career, who best got to the heart of the issue during the famous Calhoun-Webster Debates of 1850 (Calhoun was so gravely ill at the time, that he had to be carried into the Senate Chamber on a stretcher):

?That the Government claims, and practically maintains the right to decide in the last resort, as to the extent of its powers, will scarcely be denied by any one conversant with the political history of the country. That it also claims

the right to resort to force to maintain whatever power it claims, against all opposition, is equally certain?Now, I ask, what limitation can possibly be placed upon the powers of a government claiming and

exercising such rights? And, if none can be, how can the separate governments of the States maintain and protect the powers reserved to them by the constitution?or the people of the several States maintain those which are reserved to them, and among others, the sovereign powers by

which they ordained and established, not only their separate State Constitutions and Governments, but also the Constitution and Government of the United States? But, if they have no constitutional means of maintaining them against the right claimed by this Government, it necessarily follows, that they hold them at its pleasure and discretion,

and that all the powers of the system are in reality

concentrated in it. It also follows, that the character of the Government has been changed in consequence, from a federal republic, as it originally came from the hands of its

framers, into a great national consolidated democracy.?

Calhoun was correct in his logical assertion: power that is held only at the behest of a higher authority signifies no power at all. To acknowledge a political system whereby the federal government supercedes all state authority is to relegate the states a status as little more than adjuncts to federal authority, a proposition the framers of the Constitution would have found ludicrous.

Furthermore, it is interesting to note that the idea of secession was not something first advocated by the CSA, in fact, it was contemplated on more than one occasion by various regions of the nation. For example, New England twice considered secession, first in 1814 when New England threatened to leave the Union due to economic fallout from the War of 1812, and again later when John Quincy Adams argued for the secession of New England in opposition to admitting Texas to the Union. This demonstrates that state sovereignty was not a crutch for Southern aspirations, but a form of legitimate political redress recognized by the entire nation.

Unfortunately, the de facto, if not de jure, end to States? Rights would come from the very war that the doctrine was used to justify. States? Rights had become synonymous with Southern slavery and secession, and, as such, was quickly cast to the wayside by a victorious North. After the end of the Civil War, the United States Supreme Court, along with an expanding federal government, had begun chipping away at the Tenth Amendment, rendering it little more a political lame duck all but put out of its misery. Unfortunately, the process continues to this very day (the most recent example being Roper v. Simmons whereby the court has now decreed that states are incapable of even establishing their own criteria for a capital offense). The very fears that so many statesmen had articulated so passionately over the course of this nation?s history have finally come to pass.

Fortunately, this nation has often proved itself to be most resilient. There is hope, and, yes, even a few signs, that States? Rights will be restored to their proper place of reverence in American political thought and jurisprudence. But for this to happen, federal authority will need to be significantly rolled-back, a process not easily accomplished as those who have power usually resist parting with it. Our hope lies, as it always has, with the American people. Once again, I defer to the comments of John C. Calhoun:

?Besides this cry of Union comes commonly from those

whom we cannot believe to be sincere. It usually comes from our assailants. But we cannot believe them to be sincere; for, if they loved the Union, they would necessarily be devoted to the constitution. It made the Union,?and to destroy the constitution would be to destroy the Union.

But the only reliable and certain evidence of devotion to the constitution is, to abstain, on the one hand, from violating It, and to repel, on the other, all attempts to violate it. It is only by faithfully performing these high duties that the constitution can be preserved, and with it the Union.?

One can hope that such incisive words as these will one day ring again across the American landscape.

Please support the Civil War Preservation Trust, an organization dedicated to preserving Civil War battlefields around the nation:

CWPT

Posted by Wargamer Scott

at 12:41 AM EDT

Updated: Wednesday, 13 April 2005 12:52 AM EDT